From modeling to lake life and back again

By: Jan Kubečka and Allan Souza, Biology Centre, Czech Academy of Sciences

Freshwater systems are smaller and less studied than marine despite the high human dependence and impact on them. Lipno reservoir is the largest reservoir in Czechia and experienced dramatic fluctuation of anglers catches recently. The available data on fishery is fragmented and still limited, and thus the CLIMEFISH BC team had to cope with this challenge by processing the available data as well as acquiring more information that could help to develop an optimization on fishery activity in the reservoir. Available data comes mostly from the angling catch statistics, which are relatively detailed in Czechia (every angler has to record every visit of the lake and every fish he or she retains) but still not detailed enough to explain the events in fish populations. Fortunately there were also unprocessed data from ichthyological surveys performed between 1990 and 2012. These were supplemented by new 2016 and 2017 surveys of the fish stock of Lipno so we can compare historical and recent state and parametrize the models by realistic parameters like growth and survival rates, species proportions and relative abundance.

This is easier to say than to do. The survey of the largest Czech lake takes over a week work of an experienced crew (figures). Assessing of all species and size groups on all important parts of the reservoir requires of catching a processing of some 30 thousands fish every year. From many of them, the samples of gut content and age and growth recording structures have to be taken.

Fig. 1 One of the gillnet boats departs for evening setting of nets,

Fig. 2. The flagship Thor Heyerdahl equipped for hydroacoustic and trawling sampling.

Fig. 3 Sorting of the gillnet catch

Fig. 4: The main fish processing units, where fish are being measured, weighted, sexed, and many detailed samples are being taken.

An unexpected obstacle was encountered with fish growth analyses. We found that the yearly marks are best seen on the otoliths of target percid fish. The otoliths were carefully removed and inspected under the microscope. Radiuses to year marks were measured and common length backcalculation models were applied. We were surprised to see that common length backcalculation models give unrealistic calculated fish lengths. This led us to analyses of the relations between the fish sizes and various dimensions of the otoliths. It was found that in some reservoirs including Lipno, this relationship is not linear or logarithmic as commonly assumed but it is sigmoidal much better described by logistic model. These difficulties brought us also to the question of what dimension of the otolith is actually the best. In order to understand this surprising result we explore the shape of otoliths using recent developments in shape analysis. We are establishing an otolith database that is allowing us to have better insights of the reasons related to the otolith and fish length relationship. The model species for this task is the perch (Perca fluviatilis) and we detected ontogenetic shape dissimilarities as well as differences among ecosystems. These results suggest that this issue might be more important and more widespread that previously thought.

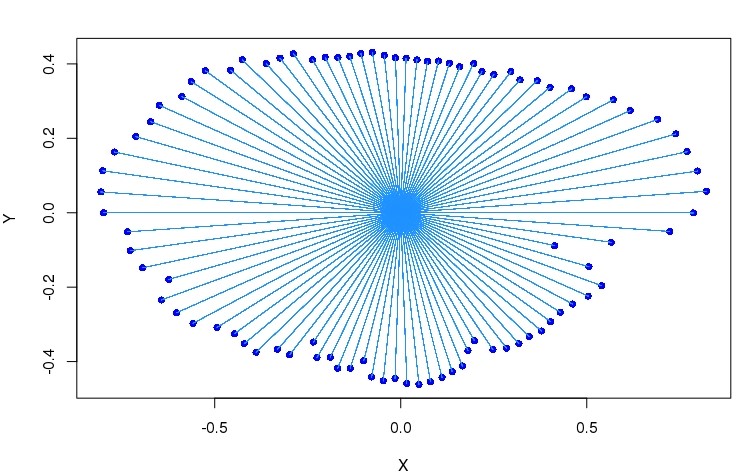

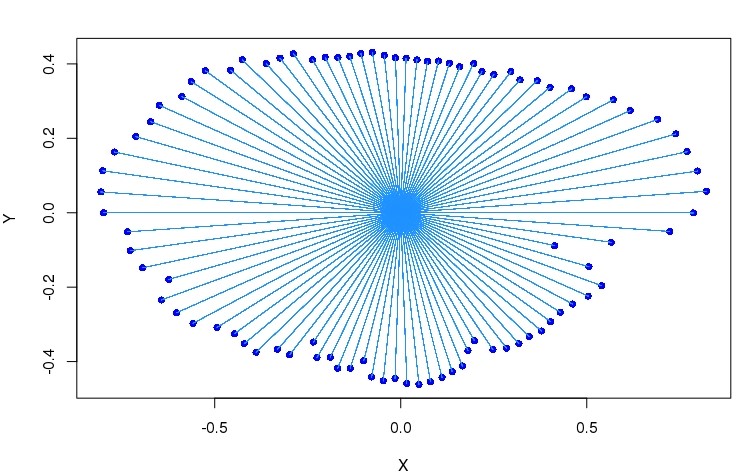

Fig. 5: Example of a perch otolith contour extraction. Red line is the 2d shape of otoliths and the green arrow indicates the distance to the otolith center to the tip where it has the highest radius.

Fig. 6: Spatial vectors indicating the distance from the geometrical center of the otolith to the border of the otolith.

Explaining the population events in a large lake reminds detective Investigation and this case shows that it is difficult to predict at the start what clues need more attention. To come back to our original task to provide good growth rate data for the population and individual based models, we had to go a long loop through the methodology of growth allometry. However, now the length-at-age data for our models are greatly improved, we can trust them and we can see the climatic signal together with the influence of nutrients in the lake. So after this extensive excursion into growth methodology we are coming back to the predictions of what will happen to percid game fish if the climatic scenarios go ahead and what fish yields can the fishermen expect.